This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

NASHVILLE, Tenn. — Most of the guys come straight to the shop each afternoon. After long shifts at supermarkets and home improvement stores, they make their way to southwest Nashville just before 4 p.m., sometimes still in uniform, and pull into a massive parking lot shared by the local community college and the Nashville branch of the Tennessee College of Applied Technology, or TCAT.

Some might rev their engines and do a few laps around the mostly clear lot first, but they all eventually take a right toward the garage.

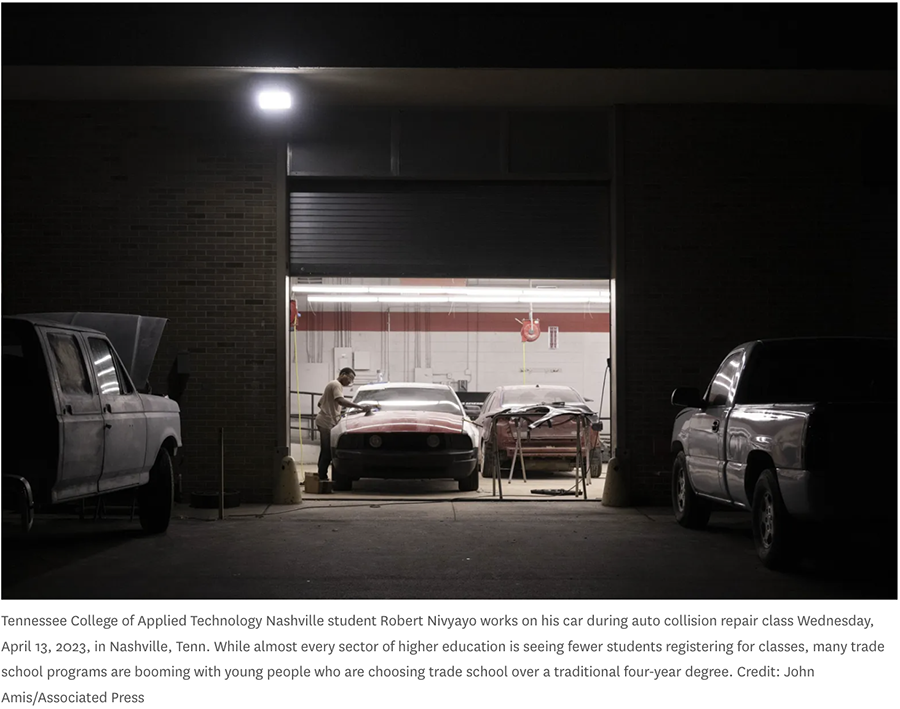

There, as the sun begins to set on a 70-degree February day, the students in the auto collision repair night class are preparing to spend the next five hours studying.

One is sanding the seal off the bed of his 1989 Ford F-350, preparing to repaint. Another, in his first trimester, is patiently hammering out a banged-up fender, an assignment that may take him weeks. Another, who has strayed in from the welding shop, is trying to distract the guys in the program he graduated from months before.

Some others linger around a metal picnic table in the parking lot, sipping cool sugary drinks and poking fun at each other’s projects. Among them is 26-year-old Cheven Jones, taking a break from working on his 2003 Lexus IS 300.

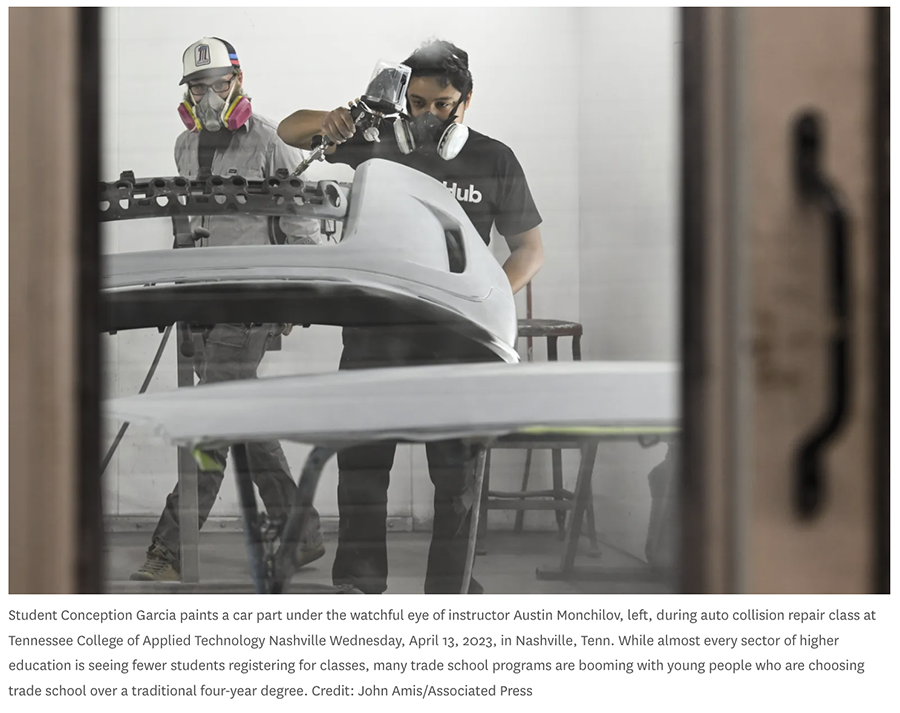

While almost every sector of higher education is seeing fewer students registering for classes, many trade school programs are booming. Jones and his classmates, seeking certificates and other short-term credentials, not associate degrees, are part of that upswing.

Mechanic and repair trade programs saw an enrollment increase of 11.5 percent from spring 2021 to 2022, according to the National Student Clearinghouse. Enrollment in construction trades courses increased by 19.3 percent, while culinary program enrollment increased 12.7 percent, according to the Clearinghouse. Meanwhile, enrollment at public two-year colleges declined 7.8 percent, and enrollment at public four-year institutions dropped by 3.4 percent, according to the Clearinghouse.

Many young people who are choosing trade school over a traditional four-year degree say that they are doing so because it’s much more affordable and they see a more obvious path to a job.

“These kids are looking for relevance. They want to be able to connect what they’re learning with what happens next,” said Jean Eddy, president of American Student Assistance, a nonprofit dedicated to helping students make informed choices about their educations and careers. (ASA is one of the many funders of The Hechinger Report, which produced this story.) “I think many, many families and certainly the majority of young people today are questioning the return on investment for higher education.”

Eddy said that the increased interest in the trades doesn’t necessarily mean these students won’t later go on to earn a bachelor’s degree, but “simply means that they are excited, and they’re more interested in getting into something where they can feel as though they are applying their skills and their talents to something that they can be good at.”

TCAT is a network of 24 colleges across the state that offers training for 70 occupations. TCAT Nashville offers 16-month to two-year courses including diesel and automotive technology and welding and construction technology, among others. Many of them have waiting lists, said Nathan Garrett, president of the college. To accommodate increased demand, the college has added night classes and is expanding shop space.

In Tennessee, the state’s overall community college enrollment took a hit during the pandemic, despite a 2015 state program that made community college tuition free. Still, at TCAT, many trade programs have continued to grow despite the downward enrollment trend.

TCAT focuses on training students for jobs that are in demand in the region, which appeals to many students in normal times, but Garrett said the pandemic may have underscored the need for workforce relevance.

“When we look at ‘essential workers,’ a lot of those trades never saw a slowdown,” he said. “They still hired, they still have the need.” Automotive trades are always in demand, he added.

“I didn’t necessarily know what I wanted to do, and my biggest fear was to go to college, put in all that time and effort and then not use my degree.” - Cheven Jones, student in TCAT Nashville’s automotive repair program

Even so, Jones’s pursuit of a degree at TCAT Nashville would perhaps be a surprise to his high school self. “My parents just basically told me, ‘Finish high school and then just work,’ ” Jones said. “I didn’t necessarily know what I wanted to do, and my biggest fear was to go to college, put in all that time and effort and then not use my degree.”

So, at 18, Jones went to work in warehouses, spending long days loading and unloading heavy boxes from tractor-trailers. But he found it unfulfilling, it was terribly difficult on his body, and he wasn’t making enough money. After just a few years, he realized he needed a job that would make him happier, hurt him less and pay him more. Trade school for a career fixing cars, he decided, seemed like the best route.

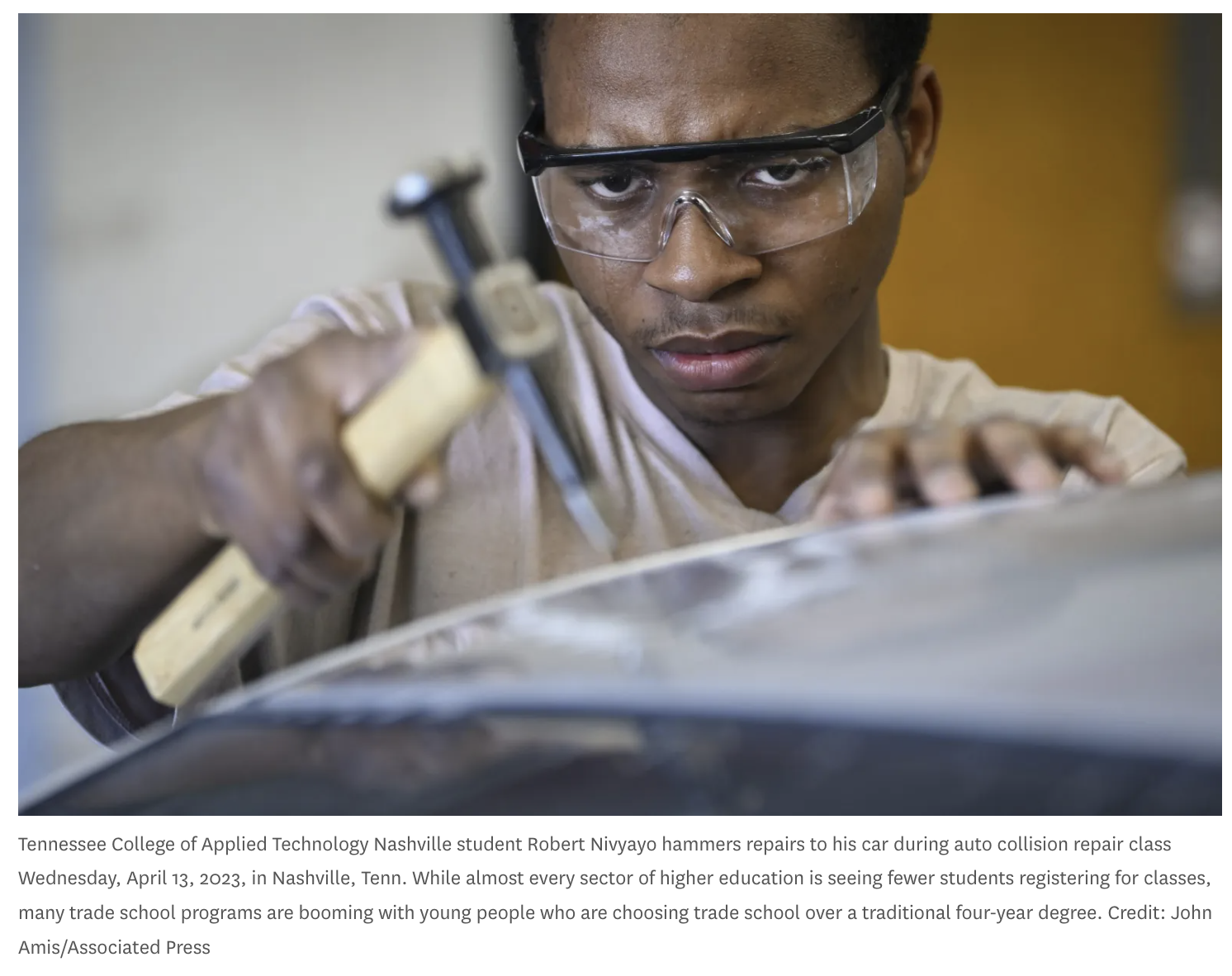

Nineteen-year-old Robert Nivyayo’s priorities became clear a bit earlier in his education, when he realized he didn’t like high school very much. He said he spent most of his free time watching YouTube videos about fixing up cars before he owned one or was even licensed to drive.

He started saving up the money he earned stocking shelves at a Publix grocery store. And around the time the pandemic hit, he bought a 2005 Mustang off Facebook Marketplace for $800 cash. It didn’t run, so he hired a tow truck to lug it to his parents’ house. He took the engine apart, outfitted it with a new head gasket and put it back together, all while his online high school classes played on his smartphone.

Nivyayo’s parents, who came to the U.S. from Tanzania in 2007, had long urged their children to go to college, he said. When he enrolled at TCAT Nashville to pursue training in auto collision repair, they were pleased: “As long as I’m going to college, that’s all they really care.”

The path made sense for him, because he could earn a credential while doing what he enjoyed, and without spending much time in the traditional classroom. He’s looking forward to the anticipated payoff, when he gets a job in an auto shop.

“I really enjoy just working on the body of the car and learning. Every new day, I just get more motivated,” Nivyayo said.

Austin Monchilov, the night class instructor, said the students are more invested in their projects if they’re working on something of their own. After they pass the initial busted-up fender assignment, they’re free to work on their own cars, he said.

Until he finishes his studies and a job offer manifests, Nivyayo is spending his evenings in the garage, picking Monchilov’s brain and taking painstaking care of every square inch of the Mustang. Even when he’s done with it, when it’s running perfectly and the silver body is pristine, he said he could never sell it. It has meant too much to him to ever give it up.

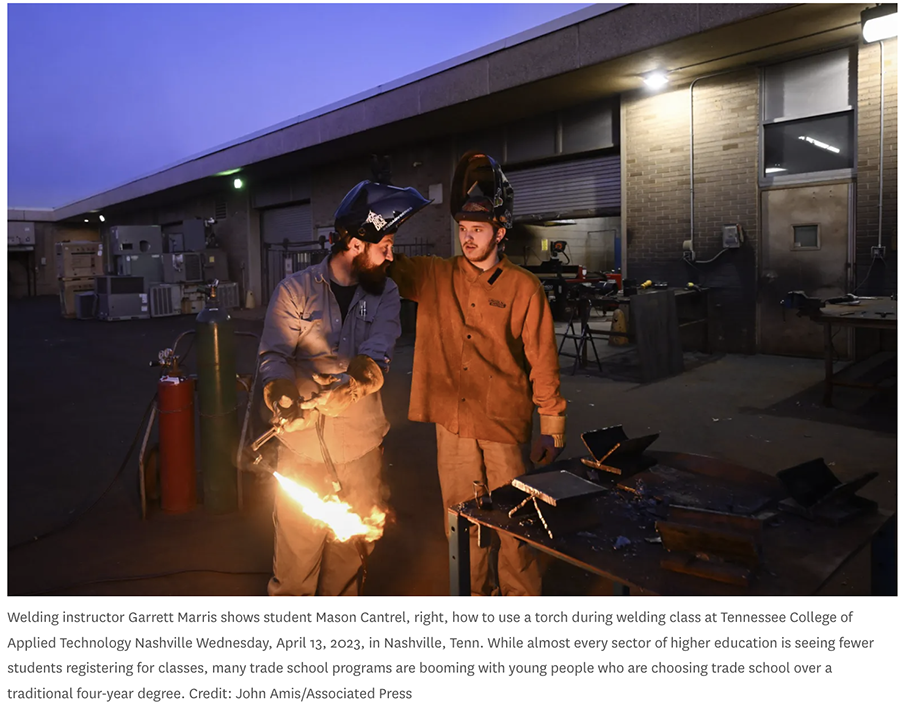

Inside the building and just a few doors down, Abbey Carlson is in the welding studio, wearing jeans with holes burnt through them and a funny cap to protect her hair. She’s the only woman in the nighttime welding class, and among few women on this side of the TCAT campus. Though welcome to enroll in these courses, women tend to congregate on the other side of the campus, where the cosmetology and aesthetics technology programs are housed.

Carlson, now 24, had initially intended to attend a four-year college, but her plans were derailed by an addiction to alcohol. After dedicating herself to recovery, she decided she wasn’t entirely done with higher education.

“I knew I wanted to do a trade, but I couldn’t figure out which one,” Carlson said. “I’m a woman, I’m young and I’m decent looking, so the world is scary. Especially in fields with men.”

After researching her options, she concluded that welding would be the safest while also offering her the highest eventual earning potential, she said. So far, she’s enjoying her time at TCAT Nashville, and she feels respected and safe.

“I love it so much. I finally have hope for the future,” Carlson said. “Finally, I feel like I’m going to accomplish something in life.”

Still, it’s not easy. Before she reports to the welding shop each afternoon for five-hour stretches of studying, she spends her days waitressing at an upscale Italian restaurant in the city.

At a campus in Shelbyville, about 60 miles south of Nashville, Jesus Pedraza, 18, is making the best of his plan B.

Pedraza thrived in high school and dreamed of studying electrical engineering at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. But when his mother started having medical challenges last year, he decided to stay in Shelbyville with her. His high school was so close to TCAT Shelbyville that the students sometimes walked over to eat breakfast in its cafeteria; the teachers and administrators at the high school encouraged the students to consider applying there after graduation.

After graduating from high school last spring, Pedraza enrolled in TCAT’s electrician training program. The courses equip students to work in residential, commercial or industrial settings; the curriculum is among several at TCAT Shelbyville that are seeing an increase in demand, said Laura Monks, president of the college. To accommodate all the interested people, she said they offer both day and night courses and dual enrollment for students from nearby high schools.

Now, Pedraza studies from 7:45 a.m. to 2 p.m, and then reports to a local Walmart distribution center, where he works from 3 p.m. to midnight each day.

He said he enjoys what he is learning and likes the guys in his class. But he still wonders what things may have been like at a four-year college.

“I would have loved the challenge of being in electrical engineering, you know, having to do all the schoolwork and just the idea of college life,” he said. “Sometimes I sit down, and I think how different it would have been if I was living in Knoxville right now. But at the end of the day, you know, it’s just the way life is. I mean, I wish I was also a millionaire, and I wish I drove two Lamborghinis. But it’s not the way it is.”

Monks said that one of the things that makes TCAT appealing to students is the possibility that, toward the end of their program, they will be able to work in their desired field a few days a week while also getting credit toward their diploma, a system known as a “co-op” across the TCAT system.

For Brayden Johnson, 20, who is in his fifth trimester studying industrial maintenance automation, the co-op program has given him the chance to work as an electrical maintenance technician in a local factory that makes tubes for toothpaste. He’s working the night shift, which comes with a slight pay bump, and is earning about $26 per hour.

He hopes to stay in the job after he finishes at TCAT this spring, he said.

The same co-op opportunity is offered to some students at TCAT Nashville. Garrett said students generally are drawn to the hands-on design of the courses and the general philosophy that “You need to get your hands on the equipment, you need to start building stuff, breaking stuff and then learn how to fix that stuff.”

The opportunity to get real work experience before they graduate is an extra perk. The employer reports back to the student’s instructor so they know where the student is excelling and where they are struggling, and can work on those weaknesses on the days when the student comes to campus, Garrett said.

Related: Long disparaged, education for the skilled trades is slowly coming into fashion

Cheven Jones began studying auto collision repair in September, and said that he has already made major progress, transforming his lifelong enthusiasm for cars into real, applicable skills.

And it’s showing on his Lexus, he said. So far, he’s fixed a dent in the hood, replaced an entire door and replaced part of the rocker panel (the long strip of metal under the doors).

The game plan, Jones said, is to transform his car by the time he graduates, and have fun while doing it.

“It’s school, and I take it seriously. But you know, you come here, and it just feels more like you’re at a shop hanging out with your homies all day,” Jones said. “It’s a good feeling.”

After he graduates, he hopes to get a job in an auto body shop.

And he says he’ll keep working until someday he can afford a red 1982 Nissan Skyline R31, RS Turbo with bronze wheels — his dream car. Even if he can’t get one in perfect condition, at least he’ll know how to fix it up.

This story about trade school programs was produced by The Hechinger Report, as part of the series Saving the College Dream, a collaboration between Hechinger and Education Labs and journalists at The Associated Press, AL.com, The Christian Science Monitor, The Dallas Morning News in Texas, The Seattle Times and The Post and Courier in Charleston, South Carolina. Sign up for Hechinger’s higher education newsletter.