A special exhibition of work by artist James Turrell is currently on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. The exhibit is titled The Light Inside and displays amazing spaces created using light as the primary component of each work. The physical rooms which contain each piece called for precise and detailed construction because they are indeed part of the art itself. Before visiting the exhibition, I talked with some of the men from Marek Brothers Systems, Inc. who worked with Linbeck, the general contractor, on the construction of these “rooms.”

A special exhibition of work by artist James Turrell is currently on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. The exhibit is titled The Light Inside and displays amazing spaces created using light as the primary component of each work. The physical rooms which contain each piece called for precise and detailed construction because they are indeed part of the art itself. Before visiting the exhibition, I talked with some of the men from Marek Brothers Systems, Inc. who worked with Linbeck, the general contractor, on the construction of these “rooms.” Turrell is known for creating spaces which he calls “Ganzfelds.” The word means “complete field” in German, and in these spaces, Turrell attempts to blur the viewer’s perception of horizon and dimension. He wants the viewer to experience these spaces with “no up, no down, no left, and no right.” In a special edition of Arts InSight which aired on Houston’s PBS television station on June 27 (DVD available for purchase - search keyword "Turrell"), Turrell explained:

Turrell is known for creating spaces which he calls “Ganzfelds.” The word means “complete field” in German, and in these spaces, Turrell attempts to blur the viewer’s perception of horizon and dimension. He wants the viewer to experience these spaces with “no up, no down, no left, and no right.” In a special edition of Arts InSight which aired on Houston’s PBS television station on June 27 (DVD available for purchase - search keyword "Turrell"), Turrell explained:

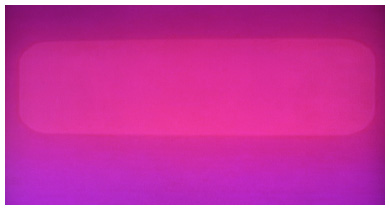

“The Ganzfeld has more to do with how we perceive form. When not given form to see, we tend to make it. That is something I am very interested in moving into: this idea, this realm of a new landscape that has no horizon. We are moving into that when we fly and get involved in flight through cloud or fog or at night, as what happened to JFK, Jr. It’s a territory that we have entered through flight, through space, through diving. I think it is a little bit exhilarating. Those spaces, when you step up to them, give you a slight disequilibrium. You have a little difficulty sometimes with balance. But I don’t leave you there for too long.” Turrell began thinking about light in a special way as a child when his grandmother would take him to church. She told him “You go inside to greet the light.” As an artist, Turrell invites the viewer to do the same with his works. Instead of using paint to depict light, he uses light itself. But for those interested in construction, what is most interesting is what you don’t see. In fact, the excellent work of the contractors and subcontractors is essential to the success of the exhibit.

Turrell began thinking about light in a special way as a child when his grandmother would take him to church. She told him “You go inside to greet the light.” As an artist, Turrell invites the viewer to do the same with his works. Instead of using paint to depict light, he uses light itself. But for those interested in construction, what is most interesting is what you don’t see. In fact, the excellent work of the contractors and subcontractors is essential to the success of the exhibit.

I sat down with Cary Seabolt, a drywall project manager at Marek and the point of contact on this project, to learn about what this particular job involved. He said,

“This was likely one of the most unique projects Marek has done. It is a 22,000 square foot area. We could not damage or attach to any of the existing surfaces. We had to build – I call them “pods” or “rooms” – that you go into to experience the art. It was a very complicated project. ... The walls actually become the art. Typically in a museum, you would go in and build a new wall and they would hang prints on it. On this project we were actually building the art. Our wall actually becomes the art and what you experience is the room that we built. So [the artist, James Turrell] shines intense lighting onto our walls and it messes with your mind.” Cary and I were then joined by Marcus Bollom, project executive at Marek, who explained how building this project differed from other projects because of the way they had to work with the artist and his representatives:

Cary and I were then joined by Marcus Bollom, project executive at Marek, who explained how building this project differed from other projects because of the way they had to work with the artist and his representatives:

“Normally an owner has a concept, the architect takes that idea and puts it onto paper, and then we contractors focus on what the architect has interpreted. [The architect] has interpreted what [the owner] has voiced – their functional needs, their aesthetic needs – an architect is trained to take that and put it on paper and we build from that. In this project we worked more closely with the artist, so things were always changing. He had a lot of things that were in his head that he knew he wanted to get out. It’s in his head, so transforming what he has in his head as the owner could not be interpreted by an architect, because interpretation muddies the art. It was up to the contractors to understand – as we build this, ‘You tell us if we are building this in the direction that your vision is taking you.’”

They had to constantly check back with the artist’s representatives to be sure that they were working in the right direction, and if not, to make the necessary corrections. He said that normally everything is “black and white” – projects are specifically drawn on paper and that is how the contractor builds them. If the finished product does not match the drawing, then it is considered a mistake and the contractor pays for the correction, but if the owner has asked for a change which is different from the drawing, then the owner pays for the rework. Working with the artist on this project, however, was different. There were no exact drawings to compare to the finished project because some of the details were in the mind of the artist. Marcus said:

“It relied on a relationship of trust. If we made the mistake, on our understanding of what we built, then the trust is that we will own up to that. But we are also trusting [the artist] that if we didn’t do that, [the artist] will understand that as well.” When an installation of any Turrell work is constructed, the contractors must work closely with the construction team from New York who represent the artist. The New York team ensures that the construction meets the exact standards required by the artist and which are essential for the intended visual effects to succeed. They customarily visit each installation five days before its scheduled opening, expecting to find the project behind schedule and in need of many corrections. At the private opening of the exhibit in Houston on June 11 for certain members of the museum, the construction team, the press, etc, Willard Holmes, associate director of administration at the museum, shared something with Mike Holland, Division President at Marek Brothers Systems, Houston. Holland described the conversation:

When an installation of any Turrell work is constructed, the contractors must work closely with the construction team from New York who represent the artist. The New York team ensures that the construction meets the exact standards required by the artist and which are essential for the intended visual effects to succeed. They customarily visit each installation five days before its scheduled opening, expecting to find the project behind schedule and in need of many corrections. At the private opening of the exhibit in Houston on June 11 for certain members of the museum, the construction team, the press, etc, Willard Holmes, associate director of administration at the museum, shared something with Mike Holland, Division President at Marek Brothers Systems, Houston. Holland described the conversation:

“Willard was told by the construction team for Turrell that they had done over 200 of these exhibits, and each time the construction team arrives five days in advance. They do this because they know that everyone who builds these will be behind schedule, and they also then tell the local team what standard of construction they want, but have never before received. Basically they come down and tell the local construction team everything that has been done wrong and the quality standard that they expect. [Turrell’s contractor] showed up here these five days in advance, and not only was the job virtually complete, but he went to Willard and apologized for what he had said earlier. He said that in over 200 exhibits that they had constructed, he had never seen the quality of the corners – and basically the work that we did – he had never seen that quality before, which caused him to retract his comment. He went on in a number of different ways to describe the quality and professionalism of The Team – the majority of which the craftwork was done by our framers, hangers, finishers, painters, and floor guys.”

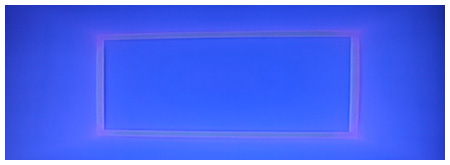

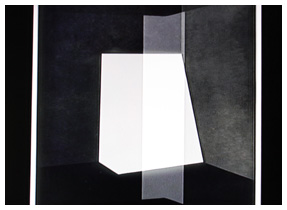

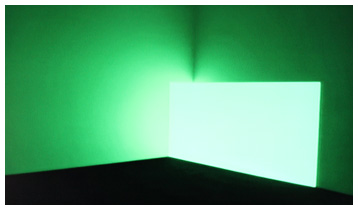

Holland talked about what he experienced when he visited the exhibit. He said that unless you were a member of the team that built this project, you might not appreciate the complexity of the  construction. You might walk into the exhibit, and see a few “simple” rooms. If you were told how many man-hours it took to put the exhibit together, you might wonder what was so complicated about this construction project. But the magic of the art lies in what you don’t see. When you realize that you appear to be walking into a room without corners, or that you believe that you are viewing a three-dimensional object rather than a flat, solid-colored wall reflecting projected light, you then realize that the precision of the dimensions of the structure and the seamless appearance of the connections are what allow the illusion to be effective. In Turrell’s enormous Ganzfeld titled “End Around,” the floor curves up and blends into the walls which curve over to become the ceiling. Viewers (who first remove their shoes and don disposable slippers) actually walk on drywall instead of on a traditional flooring material. In addition, although the “floor” is flat, it is not completely level. The subtle “disequilibrium” Turrell described in the PBS interview is experienced as a pleasing sense that one is floating immersed within the art. Holland put it, “You realize that you are walking on the art and that the construction work is truly a part of the art.” The time-consuming detail which Marek put into the project is precisely the part of the art which is not “seen,” but which is the mechanism that allows the viewer to experience what Turrell envisioned.

construction. You might walk into the exhibit, and see a few “simple” rooms. If you were told how many man-hours it took to put the exhibit together, you might wonder what was so complicated about this construction project. But the magic of the art lies in what you don’t see. When you realize that you appear to be walking into a room without corners, or that you believe that you are viewing a three-dimensional object rather than a flat, solid-colored wall reflecting projected light, you then realize that the precision of the dimensions of the structure and the seamless appearance of the connections are what allow the illusion to be effective. In Turrell’s enormous Ganzfeld titled “End Around,” the floor curves up and blends into the walls which curve over to become the ceiling. Viewers (who first remove their shoes and don disposable slippers) actually walk on drywall instead of on a traditional flooring material. In addition, although the “floor” is flat, it is not completely level. The subtle “disequilibrium” Turrell described in the PBS interview is experienced as a pleasing sense that one is floating immersed within the art. Holland put it, “You realize that you are walking on the art and that the construction work is truly a part of the art.” The time-consuming detail which Marek put into the project is precisely the part of the art which is not “seen,” but which is the mechanism that allows the viewer to experience what Turrell envisioned.

Watch more of my conversation with Cary and Marcus in the 9-minute video below.

The Light Inside is being displayed this summer in conjunction with two other Turrell exhibitions which are being shown in Los Angeles and in New York. The exhibition in Houston will be on display through September 22.

The Art of Construction [VIDEO]

by Elizabeth McPherson | July 03, 2013

Add new comment